Research

One of the central questions that drive our research is ‘How does cellular complexity increase?’ The origin of the eukaryotic cell represents the most drastic structural re-organization and increase in complexity throughout cell evolution. The acquisition of intracellular symbionts, and the origin of symbiotic organelles such as mitochondria and chloroplasts, are further examples of significant increases of genetic, metabolic, and cellular complexity.

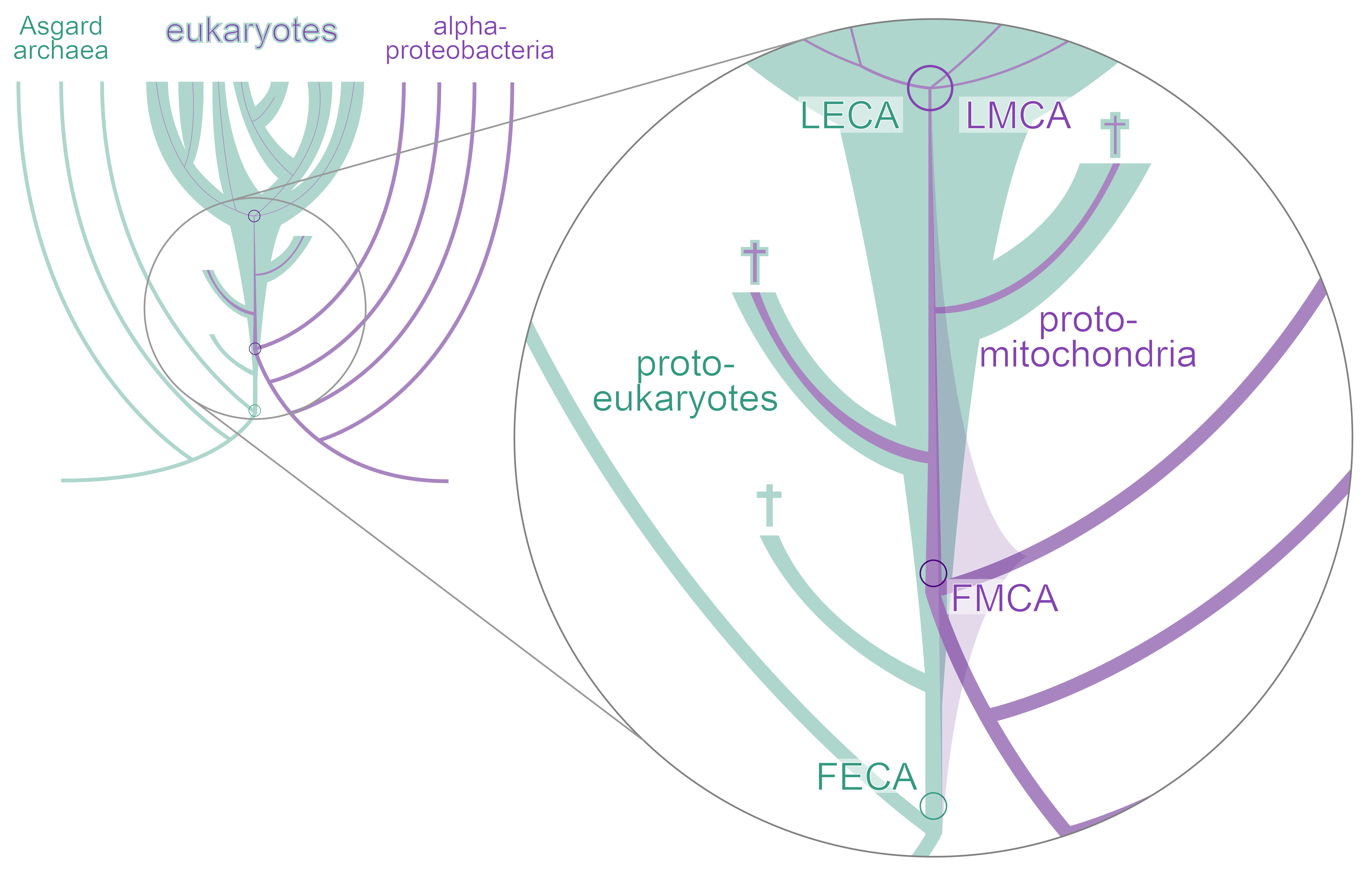

The origin of eukaryotes and their mitochondria

The transition from prokaryotic to eukaryotic cells is often thought to be the greatest transition in the history of life. This is because this is the largest gap, or discontinuity, in organismal structure or organization across the tree of life: eukaryotic cells are structurally much more complex, and on average, also larger in volume than prokaryotic cells. Eukaryotes also gave rise to all complex multicellular life on our planet (e.g., animals, plants, kelps). Prokaryotes, on the other hand, have comparatively evolved little cellular complexity and only a few cell types in simple multicells. We are interested in understanding how and why prokaryotes evolved into eukaryotes. Our past research has focused on understanding the origin of mitochondrial cristae (see Muñoz-Gómez et al., (2015) Curr. Biol., 25(11):1489-1495 and Muñoz-Gómez et al. (2017) Mol. Biol. Evo. 34(4):943-956), the phylogenetic placement of the mitochondrial lineage (see Muñoz-Gómez et al., (2021) Nat. Ecol. Evol. 6:253–262), and the role of mitochondrial energetics at the origin of eukaryotes (see Schavemaker & Muñoz-Gómez (2022) Nat. Ecol. Evol. 6:1307–1317). Some of the questions we are currently trying to answer are:

- What was the nature of the mitochondrial ancestor?

- What was the genetic contribution of the mitochondrial ancestor to eukaryotes?

- How did mitochondria affect the physiology and evolution of eukaryotes?

Methods: Large-scale phylogenetics; comparative genomics; bioinformatics; metagenome sequencing and analysis.

Purple photosymbioses

Symbioses between heterotrophic and photosynthetic organisms (photosymbioses) are very common in nature (e.g., lichens or corals). Virtually all of these photosymbioses involve oxygenic photosynthesizers: organisms that release oxygen as waste while using sunlight to produce their own food. On the other hand, photosymbioses between eukaryotes and intracellular anoxygenic photosynthesizers such as purple bacteria are extremely rare. Purple bacteria use electron donors other than water, prefer much longer light waves as energy source, and photosynthesize in the absence of oxygen. Only two examples of eukaryotes that harbor intracellular purple bacteria have ever been reported (Muñoz-Gómez & Hess (2023) Curr. Biol., 33: R159-R179). We have recently studied on one of them, the freshwater ciliate Pseudoblepharisma tenue, which also harbors intracellular green algae, making it the only eukaryote known to combine two contrasting photosynthetic endosymbionts (see Muñoz-Gómez et al., (2021) Sci. Adv. 7:eabg4102). We are interested in understanding the physiology, ecology, and evolution of purple symbioses, and ultimately want to explain why purple symbioses are so incredibly rare in nature. Some of the questions we will focus on in the near future are:

- What are the mechanistic/metabolic bases of purple symbioses?

- What are the ecological niches of purple symbioses?

- What is the evolutionary trajectory that led to the origin of purple symbioses?

Methods: Field sampling; cultivation and enrichment; physicochemical analyses; genome and transcriptome sequencing (long-read Nanopore and short-read Illumina); NanoSIMS; light, fluorescent, and electron microscopy, comparative genomics, phylogenetics.

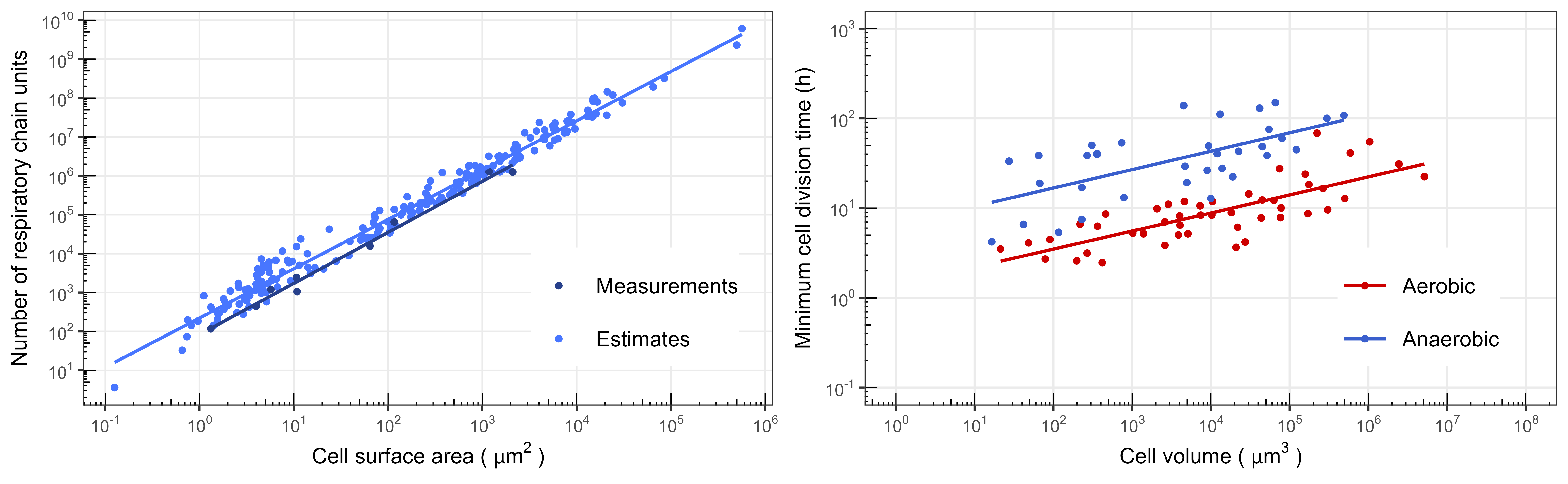

Evolutionary cell physiology

The history of cells on Earth has been marked by evolutionary transitions that encompass increases in cellular complexity, structural re-organizations, and symbiotic mergers. A plethora of hypotheses based on phylogenetics and comparative genomics have been proposed to explain how and why some of these transitions (e.g., eukaryogenesis) occurred. However, these ancient and transformative evolutionary events remain poorly constrained. We hope to unravel general physiological and biophysical principles that constrain the evolution of cells, and explain the evolutionary possibilities available to major cell body plans. Some of our previous work has addressed the scaling of respiratory membrane area across prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells (see Schavemaker & Muñoz-Gómez (2022) Nat. Ecol. Evol. 6:1307–1317), the physiological and ecological consequences of an energy-inefficient fermentative metabolism in anaerobic eukaryotes (see Muñoz-Gómez (2023) Nat. Microbiol. 8:197-203), and the micro- and macroevolutionary costs of increases in cellular complexity (see Muñoz-Gómez (2024) Trends Microbiol.). Some of the questions we want to systematically investigate are:

- What is the evolutionary relationship between energy and cellular complexity?

- What are the physiological and ecological possibilities of the prokaryotic and eukaryotic cell body plans?

- How do physiological constraints define ecological niches and dictate the ecological strategies of symbioses?

Methods: Mathematical modelling; stable cultivation of microorganisms; measurement of physiological parameters, fluorescence confocal microscopy.

Experimental evolution of symbioses

Coming soon.

Methods: Long-term cultivation of microbial consortia; genome sequencing and analysis; genetic engineering; microcosms.

Our collaborators

- Purificación López-García (Université Paris-Saclay)

- David Moreira (Université Paris-Saclay)

- Julius Lukeš (Czech Academy of Sciences)

- Hassan Hashimi (Czech Academy of Sciences)

- Paul Schavemaker (Arizona State University)

- Jeremy Wideman (Arizona State University)

- Sebastian Hess (University of Cologne)

Funding